Why do we spend so much time evaluating how well students can answer questions, yet spend virtually no time at all teaching them how to ask them?

Questions are the keys to knowledge. The ability to frame questions to access knowledge, to think critically and exercise judgement are key intellectual tools which can adapt to any workplace. The best we can predict about the future of the youngsters we are educating today is that their future jobs are unpredictable. Learning subject content will no longer be enough when no one can be certain which content of all will be relevant in their adult lives. Surely, we need to teach students to frame powerful questions now, more than ever!

When teachers ask the questions they control the direction, the pace and the scope of what is to be covered. In setting up a new course of study teachers actually learn a lot themselves by going through the process of inquiry, research, sifting and structuring information, and pulling out the fundamental questions around which to base assessments. By this stage all the interesting creative decisions have been made and all the student is left with is to copy the notes, answer the worksheets and study this regurgitated pap for the test; basically to color in the spaces in a endeavor which is as akin to genuine intellectual activity as painting by numbers resembles creative artwork.

Now don’t get me wrong, I have done as much of this kind of teaching as the rest, but the longer I do this job the more I realize that the real learning is in the struggle, in the preparation, and that if I am to help my students and equip them with the useful skills they will need for life, I need to make them apprentices in this process, and teaching the skill of asking questions is the first step.

In my classroom we have always traditionally begun units of study in science and social studies with group brainstorming sessions, charting what we know and what we would like to learn about the new topic; what is known in the trade as a K.W.L. Chart. However, students’ questions can often be quite limited as they use a “who, what, where, why, how” approach. This year an inspirational colleague, David Nelson, introduced me to the work of The Right Question Institute, and I began to realize that I could teach my students to ask much better questions.

One important factor to writing better questions is to provide a well thought out “question focus”, which can be a keyword, a phrase or a statement. This is written on chart paper and groups of students are asked to silently generate all the questions they can around this idea for about 5 mins. The only rules are to keep on writing until the time is up and not to comment, criticize or attempt to answer others’ questions. The next step is to identify open and closed questions, and to practice changing the open questions to closed questions and vice versa.

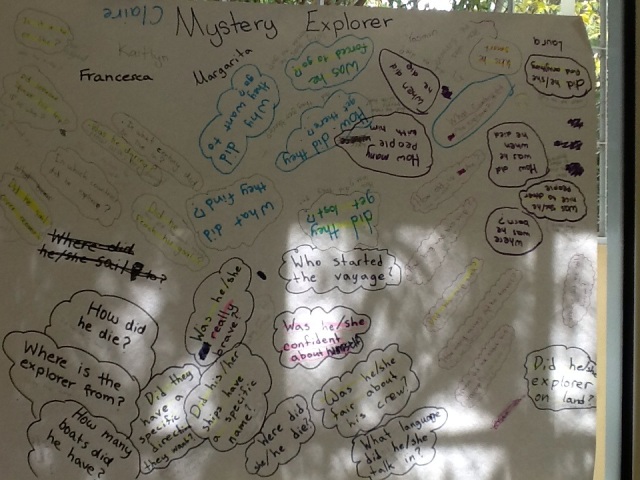

Following this plan, we wrote questions around the question focus of a “mystery explorer” before students began their research into a specific explorer of their choice. We repeated the exercise with a “mystery element” question focus before researching specific elements. These pre-research questioning sessions allowed the students to flesh out the breadth of inquiry they would need to pursue in order to give a well rounded account of their chosen subject. Certainly I could see the depth and quality of the students’ questions improving as they became more experienced in asking thoughtful questions, and they found this activity really interesting and engaging.

What I did not do, and plan to do next year, is to go through the process of prioritizing and organizing these questions with the students and have them create the research guide sheet from their own questions. At this stage in my own learning, it is still a challenge for me to truly honor the students’ questions and allow them to authentically steer the research process. If anyone reading this has experience in this area, I would be very grateful if you would contribute a comment below.

Mmmm… yum! I love this blog post! I have a copy of A More Beautiful Question in my office if you want to peek. 🙂

I think perhaps one of the best things we have done as parents to our now teenager, was always promote the asking without knowing (or having to know) the answer. He keeps a question book (since about the age of 4) and it is worth its weight in gold, I think.

LikeLike

Standardized education worked throughout the 19th century. It was a model put in place then with not too many changes up until now. Students were rewarded for memorization and not for creativity. This method in most cases is the easy way out; pick a topic, choose what is important, students regurgitate what is fed to them and then we assess them on this information. This system is no longer effective considering the speed at which society is shifting today.

If we take the Explorers unit as an example, we have to ask ourselves as teachers, what is most important about learning about the Explorers? Is it important to know when an explorer was born or how he died, what he discovered and which country he represented, (who, what, where, when and why)? When and how will this knowledge come in handy in a student’s life? What does it matter? I agree however that we need to know about our past in order to understand and create a better future.

If we want to claim that we are on board a 21st century education model, we as teachers must be more experimental in using the technology that our students see as games. For example, we can try to use a Mind Map program to help them with organizing their questions or they could develop a game using Scratch programming. As they are creating an explorer’s journey they might come up with a question like; What if Columbus and Leif Ericson hadn’t discover the Americas and ended up somewhere else on the globe? Perhaps then they will see the cause and effect of our actions as human beings and that our decisions in life can have an impact on people around the world.

LikeLike

You address a number of fundamental issues here in your discussion of formulating questions as a key to critical thinking. I contend that this is a life skill and not just training for the workplace since it is necessary for all types of problem-solving. Research is solving an information problem, an academic activity when conducted at school, but people of all ages do research everyday. Since we have elections coming up, I’ll use this as an example. Voters do research to decide how to use their vote and formulating good questions in this process is essential!

As educators, the strategy you describe for educating (rather than training) students requires us to become comfortable in the role of facilitator rather than disseminator of knowledge. We have to take calculated risks and evaluate the outcomes. Of course, the implications for assessment are enormous, too. In a recent video for the WISE foundation, Noam Chomsky relates an anecdote about a colleague of his at MIT. This physicist was teaching the freshman course and inevitably the first day of class one of the students asked what he was going to cover in the course. His stock response was, “It doesn’t matter what I cover. What matters is what you discover.” The process of students generating authentic questions and using a variety of tools to find the answers leads to discovery! Chomsky asserts, “That’s what teaching ought to be; inspiring students to discover on their own, to challenge if they don’t agree, to look for alternatives if they think there are better ones, to work through the great achievements of the past and try to master them on their own because they’re interested in them.”

Wouldn’t it be interesting to prepare for a field study by having students formulate their own questions and look for the answers on-site? What might be a tedious process of organizing and prioritizing questions if done beforehand becomes a natural part of the investigation after data has been gathered from the site and other sources. It is also highly individualized approach and can lead to a collaborative outcome.

LikeLike

The discussion you have provoked here, Penny, shows how significant is this question of questions.

It brings home how central is the social context : how we need to maintain children’s confidence that an exploration starting from no answers is is no bar, is normal really; that acknowledging mistakes and bafflements is normal too! We are concerned to develop confident purposeful searchers. And Jan is right to remind us that this is not confined to preparation for work, but is a practice for everything.

One of the most destructive subliminal messages in your average classroom, the world over, is the daily assumption that teacher is the questioner firing out of a fortress of knowledge.Mysteriously this grown up in the room has acquired immaculate expertise.

I trialled investigative learning in secondary school decades ago. New to teaching, I tried giving pupils as a starter, Kipling’s rhyme on his job as investigative journalist:

I had seven little serving men

They taught me all I knew

Their names were which, why, where and when

And how, and what, and who.

It was a while before I realised that of course we already have these concepts along with language. It was not a set of external tools my children needed, but purposeful contexts to provoke use of them. The rhyme was only a useful afterthought sometimes in reviewing whether we had overlooked an interesting line of enquiry. David

LikeLike